Andrew Facciolo only lasted just over a year on the job. That was all he could bear.

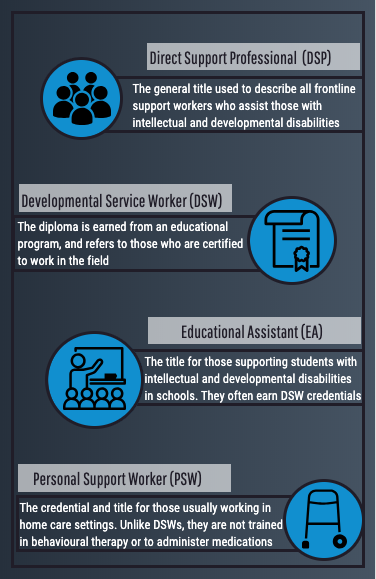

He was a “direct support professional” and at the age of 25, he was already burnt out.

It’s a common refrain among such professionals, formally known as developmental service workers (DSWs). And at a time when caseloads are growing and resources are shrinking, the issue of DSW burnout is creating a perfect storm for the developmental services sector in virtually every part of the country.

Andrew vividly remembers the days of violence. On one occasion, someone he supported broke household items and then repeatedly banged their own head against a door frame.

“I actually felt like I was in a horror movie,” Andrew said. “He got to the point where he was so emotional that he was able to just break everything.”

Andrew was employed as a full-time direct support professional, supporting people of all ages with mental and physical disabilities. He had been working in a residential home for Reena, a community living organization just outside Toronto, for almost a year, when the work slowly started to become unbearable.

He’d start the work week filled with dread, already knowing what to expect. The man he helps support will act out, be arrested by the police and driven to the hospital, only to later return with a list of prescribed medications.

Three days later, these events will happen again. It had become a highly predictable and highly stressful pattern.

“It was just like this repetitive cycle that would drive you crazy, because no one knows what to do,” Andrew said. “You’re the only person, they’re (police officers, hospital staff) basically saying ‘here, this is your job, do it.’”

Andrew doesn’t remember the man’s diagnosis, but he knows it was complex. Coming from another institution — asylums operated by the government for people with disabilities — this client had initially transitioned seamlessly into the residential home. But several months into Andrew’s employment, the client went into crisis almost every day.

“It just felt like a constant revolving door of violence,” said Andrew. When the man became frustrated, the support workers were to make sure other residents in the home were safe and then lock themselves in the staff room.

Instances that stick out for Andrew are those where the client broke items in the home or harmed himself, often leaving blood everywhere.

“At that point for me, it’s just like wow this is not essentially what I signed up for. I mean, I did it to help people. I did it to aid in people’s progress,” said Andrew. “But when you go to work every single day and it’s almost just like whatever you do is not progressing, it’s just escalating or going downwards, it’s like okay, is this for me? Do I really love this? Is this what I’m supposed to do?”

At the time, Andrew was one of over 21,000 frontline support workers estimated to be employed at community living organizations in Ontario’s developmental services sector. That doesn’t include the number independently hired by families for at-home care.

More importantly, Andrew is also part of an unknown number who have left the sector, due to burnout.

Andrew’s experience may seem extreme, but challenging and aggressive behaviours are quite common and are one of the many causes of burnout in this workforce. Other contributors to burnout relate to the conditions of the job, specifically low pay, part-time hours, intense workloads, and poor organizational culture and employee relations.

Data on the percentage of workers within Ontario’s developmental services sector who have experienced burnout and subsequently left their jobs does not exist. But research that has surveyed a portion of the workers, along with insight from labour relations experts, acknowledges that the workforce is in crisis – one that’s expected to become worse as the demand for these services increases and workers continue to leave.

This isn’t new information.

The Ministry of Children, Community and Social Services, which funds these organizations and supports more than 70,000 Ontarians with disabilities, has been aware that burnout, turnover and low retention rates are problematic.

Yet insufficient funding and inadequate policy adjustments leave the workforce at a standstill.

Though about 70 per cent of the workforce is unionized, union regulation and advocacy haven’t done enough to improve working conditions in the sector. Additionally, a lack of public knowledge about the role of developmental service workers means they are perpetually undervalued within society.

Clocking In

Back when Vito Facciolo, Andrew’s father, started out as a support worker in 1968, people with disabilities lived in institutions. On any day, Vito would care for as many as 50 people alongside two or three other workers.

After 51 years in the field, Vito is now the executive director at the Community Living Association of South Simcoe (CLASS) in central southern Ontario. Before the province’s last institution closed in 2009, Vito said that support workers prioritized meeting basic care needs and managing difficult behaviours.

Today, the care provided is much more individualized.

Approximately four to six people live in one home where a team of workers provides support and is more involved in the social aspects of each person’s life.

“There’s a higher order expectation and that is the frontline worker today should be the support medium that will take people to try and achieve their potential,” Vito said. “What we do here is we become facilitators so that people can become better people.”

This is the mantra of the community living association he oversees, and one that he instilled in Andrew when he joined the field.

At CLASS, one of Ontario’s 360 non-profit developmental service agencies, a day in the life of a support worker can look very different across the organization. Both Kailey Flear and Jenny Druery are support workers at CLASS, but while Kailey runs the day program at one home, Jenny supports the day-to-day lives of residents at another.

Each workday, Kailey arrives at a residential home in Bradford around 8:30 a.m. From the outside, it’s an average house equipped with accessibility ramps. But inside, there’s lots of commotion. Every few minutes the doorbell rings as someone new arrives and gets settled. People come to the day program to socialize with others, learn new skills, volunteer, and take part in different activities and events.

But on most days, it’s just about learning to complete daily tasks.

“It can be something as simple as like putting on a seat belt, you know, and it could take like, weeks, or helping them with the laundry, showing them how to do that, and just those things that will sort of improve their lives,” said Kailey.

“With individuals with disabilities, you’ll notice that people kind of pigeonhole them and automatically assume that they can’t do things. So, a lot of times, I’ll take that upon myself to try to help show them, and whoever else, that this is possible.”

Meanwhile, less than a five-minute drive away, direct support professional Jenny provides at-home care and is getting people ready for the day. Most of those at the home she works in have challenging behaviours and require 24-hour support.

Jenny has been in developmental services for almost four years and joined CLASS five months ago. She arrives with her day team coworkers at 9 a.m. to complete daily household tasks, prepare meals, and provide personal care, such as getting people dressed or showered. Depending on the weather and the day’s schedule, Jenny and her team may take clients out for a drive or a walk.

But Jenny is doing all of this while managing the difficult behaviours that often arise.

“It could start with someone smacking their leg, and then jumping around, to trying to spit at you, hit you, or scratch you,” said Jenny. “Some days, you see the behaviour and you de-escalate, so you’re good. But some days, you can’t de-escalate. And then you have to evacuate other clients and let the behaviour run its course.”

Challenging behaviours are usually disruptive or inappropriate, and can include tantrums, disobedience, aggression towards objects, self or others. Individuals who express themselves in this way may have an underlying mental health issue, a complicated diagnosis, or have no other way to convey their stress and frustration. Either way, Jenny needs to realize when something’s wrong and try to mitigate any harmful reactions.

At CLASS’s main centre in Alliston, Tori McLellan is one of the senior support workers who helps run both a day program and an after-school program. She arrives at work around 7:30 a.m. and picks up the people attending the day program in a 24-seater bus. Each day has a schedule, one that includes volunteering at local elementary schools, skating rinks, and non-profit organizations. Other activities include going to the gym, bowling, swimming, the movies, or to the library.

Though managing these activities with large groups can be quite difficult, Tori says helping people maintain a relationship with their community is the best part of her job.

“They’ve made connections, because we’re out in the community. And those connections have changed their life,” said Tori. “They’ve become a member of their community, they’re not just ‘that person that’s supported at CLASS.’”

At the same time, these outings can be the most difficult part of her job, especially when clients get frustrated because they don’t want to participate in the activity on that day. Often, Tori is managing these behaviours in a public setting, trying to calm the person down while making sure she is keeping herself and others safe.

By the time Tori is finishing up her day around 4 p.m., Emily Downes’ has only just begun. A few streets away from the resource centre at a residential home, Emily arrives for her evening shift as a part-time support worker. Emily gets in right in time for dinner, which is when she administers medications and helps organize evening activities.

“People don’t understand like what we really do. I think there’s a huge lack of education,” Emily said. “You are go go go all the time.

For example, if some of the individuals don’t go out tonight, they will just sit and watch TV. But, you’re not just sitting and watching TV, you’re answering a billion questions, you’re repeating yourself a billion times.”

Emily said that one of the people in the home obsesses over wrist watches and sometimes thinks there are watches under the couch. In one shift, Emily will have to move the couch repeatedly to show the client that there aren’t any watches there.

By the end of Emily’s shift at 9p.m. everyone is in bed, and she switches out with the overnight staff.

In addition to each unique diagnosis, habits and behaviours, there are diets, allergies, medical appointments and medications to track. Support workers are also expected to assist individuals with their personal lives – support their personal goals and choices, help them manage relationships with their family and the community, keep track of their finances, teach them new skills, and advocate for them within society.

Though Kailey, Jenny and Emily each have post-secondary education, Tori is the only certified developmental service worker. This is highly representative of Ontario’s current workforce, where, as of 2017, only a quarter of agency-based workers had DSW diplomas.

In Ontario, working as a DSW is a designated trade that doesn’t require any credentials beyond a high school diploma. Unlike other recognized trades, which typically require mandatory schooling and a certificate, Ontario has no standardized requirements for those supporting someone with a disability.

For president and founder of the Ontario Personal Support Workers Association, Miranda Ferrier, whose son has autism, the lack of standards required to become a DSW is concerning.

“People with disabilities are as vulnerable as a senior person and they can also get taken advantage of very easily, so why are we not watching who is becoming a developmental support worker? Or who is being hired off the street?” Ferrier said.

Ferrier often speaks on issues pertaining to DSWs because they have no official association within Ontario.

She pointed out that unlike personal support workers, DSWs are managing complicated medical prescriptions.

“Well how can a non-standardized, non-regulated, non-recognized profession be administering medications? We can all have training on medications, but if you’re not accountable or responsible or licensed to do it, then don’t do it,” Ferrier said.

A lack of schooling might be contributing to the issues within the workforce.

In 2008, under the Liberal government of Premier Dalton McGunity ,the former Ministry of Community and Social Services (MCSS) created the Developmental Services Human Resource (DSHR) strategy. Its initiatives were developed from recommendations by a panel of expert stakeholders in developmental services. Over a span of 10 years, various partners helped implement the report’s strategies which were meant to advance professionalism in the field and improve the quality of services.

Pre- and post-strategy implementation survey data was collected from 3,000 agency workers, along with that of HR managers and executives from 84 agencies. This makes it the largest and most current profile of the workforce.

Findings showed that those who earned a DSW diploma reported better work experiences and felt more prepared for the nature of the work. Additionally, they had higher job satisfaction and better relationships with their supervisors.

Yet, more than a decade ago, college DSW programs within Ontario had such low enrolment numbers that they almost closed. Over the years, the number of applicants has improved, but maintaining apprenticeship programs remains challenging.

Unpreparedness for the workforce or knowledge about what it entails can not only impact the quality of service, but individual perceptions of the job – possibly making it one of the initial contributors to burnout.

Burning out

When Andrew burnt out, the love he had for developmental services since he was a child instantly evaporated.

Growing up, Andrew became interested in the field through his father. At 18 years old, he started doing respite work, which meant that for a few hours each week he would look after clients to give family caregivers a break.

“When I first got into it, when I thought ‘okay this is what I want to do,’ I had actually worked with an individual who, for about 10 years, had not said a word to his whole family. He was completely non-verbal and when I started working with him, it took me about six months and by the end of us working together, he was talking with his family, completing full sentences, laughing and showing emotion,” said Andrew.

“That made me feel so good, that was where the love really started.”

Andrew gained more experience by spending a few summers working at a day program for a Community Living Association in Barrie. At age 24, while enrolled in business studies at Ryerson University in Toronto, Andrew accepted a full-time support worker position at an organization known as Reena — a non-profit that has been around for nearly 50 years. Its website tells visitors that Reena “promotes dignity, individuality, independence, personal growth and community inclusion for people with developmental disabilities within a framework of Jewish cultures and values.” Reena runs more than 30 group homes and 60 “supported independent living apartments” across the Greater Toronto Area.

As a young male worker with already quite a bit of experience — uncommon in the sector — Andrew was placed in one of Reena’s most behaviourally difficult homes.

“It was tough,” recalled Andrew. “You’d like to go to work and be able to kind of leave it there, to a certain extent, but a lot of the things that I was exposed to would really follow me back home.”

Within a year Andrew began feeling burnt out and after a few more months of trying to stick it out, he quit.

What is Burnout?

Burnout is a psychological phenomenon that arises from physical and emotional exhaustion due to continuous long-term stress in the workplace. As a result, work productivity and job satisfaction decrease, and well-being might suffer.

In May 2019, the World Health Organization added more detail to their definition of burnout, labelling it as a non-medical syndrome that influences one’s health status.

Burnout is measured and felt based on three distinct components: emotional exhaustion, depersonalization and lack of personal achievement. Emotional exhaustion is when the demands of the work exceed a person’s energy levels, causing them to feel drained. The extent to which a support worker no longer cares about the people they support and blame them for their problems is known as depersonalization. Support workers may eventually get to the point where they feel like their work is not meaningful or having a beneficial impact, which is identified as a lack of personal achievement.

"It is a relationship issue, I don’t see it as a clinical syndrome at all. It’s more of an existential crisis between people and their work."

A 2013 report by Dr. Robert Hickey — a professor of labour relations at Queen’s University in Kingston and researcher of the DSW workforce — profiled Ontario’s developmental support workforce and their work experiences, including burnout. Almost 2,800 surveys were collected between 2010 and 2012, making it one of the largest global data sets on direct support workers.

Since there is no threshold value to confirm if someone is burnt out, researchers measure burnout along a continuum of low to high. Of the survey respondents in Hickey’s report, average burnout was medium to low across all three components. A majority of 57 per cent experienced low levels, 25 per cent fell mid-range, and 18 per cent had high levels.

While the report mentions that these findings are similar to those in other health and human services fields, it’s not clear how representative these values are of the entire workforce.

Causes of Burnout

Among frontline workers and workforce researchers, it’s well known that those who encounter aggression from the people they are supporting are more prone to burn out.

Research by the director of the Health Care Access Research and Developmental Disabilities program at the Centre for Addiction and Mental Health (CAMH) in Toronto, Dr. Yona Lunsky, found that of 926 surveyed direct support workers, 25 per cent were the target of aggression almost every day. Only 8 per cent had not experienced any aggression.

Within this study, aggression was defined as any verbal threats or actions that caused self-harm, harm to the worker, to others or to property. About 20 per cent of workers surveyed had experienced aggression that led them to sustain a physical injury.

Those who frequently experienced severe aggression felt more emotionally exhausted and depersonalized, with up to 24 per cent of participants burnt out or at high risk of becoming so.

Additionally, a 2012 Australian study of 108 workers found that challenging behaviour led to all three levels of burnout, with high workload being the best predictor of emotional exhaustion. Perceived low levels of supervisor support led to depersonalization, while job feedback positively influenced feelings of personal accomplishment.

In line with these findings, Andrew and many other support workers agree it’s not just aggression and challenging behaviours that make them feel burnt out.

Finite resources in the sector, staffing shortages, poor organizational culture and employee relations hold significant weight, and are all aspects of the industry that Hickey has extensively studied.

Hickey argues that these factors contribute more to feelings of burnout than the nature of the work itself. As such, he hasn’t found much evidence of depersonalization which attributes burnout to the relationship between the person being supported and the worker.

Rather, he’s found that “prosocial” motivation is a more accurate measure.

“People who are in this sector are really motivated by what we consider to be prosocial causes,” Hickey said. “The idea that their work is having a positive impact on the life of another person really drives their commitment, it drives their motivation and brings them to work every day.”

“But when you’re more prosocially motivated, you’re also more acutely attuned to the failings of the system.”

Hickey said that workers trained in “person-centered” philosophies and practices strive to make a positive impact in the field. However, inadequate resources and rigid protocols make it challenging to do so.

At the same time, feelings of prosocial motivation reduce the likelihood of depersonalization and make people want to remain in the field.

When it comes to defining the demographic most at risk for burnout, research is scattered and scarce.

A 2009 study in the U.K. of 103 direct support workers found that personality traits influence the amount of stress workers experience. This subsequently impacts their health and risk of burnout.

Though the study’s small sample size makes it difficult to know the weight of the findings, results found that neuroticism, extraversion and conscientiousness are personality traits that influence burnout.

Someone who is neurotic, meaning they have a negative mood and heightened anxiety, is more likely to experience emotional exhaustion and poor mental health, along with feelings of low personal accomplishment.

Those who were more conscientious, or who placed more emphasis on doing their work properly, were likely to experience depersonalization.

Extroverted staff, who are outgoing and enjoy the company of others, were less emotionally exhausted and felt more accomplished.

Depending on where a person falls in terms of these three traits, they will experience challenging behaviour as more or less stressful.

This study did not find that gender contributed to burnout, but others have found that it has an impact.

An important characteristic of the frontline workforce is that it is predominantly female, with a quarter of Ontario’s workforce being immigrants. Male workers tend to be more satisfied with the work, but some studies have found that they also experience depersonalization at a higher rate than women.

But with a large portion of the workforce experiencing similar issues, it’s necessary to look beyond the characteristics of the workers.

Organizations and Relationships

A lot of the initial hostility and frustration support workers feel may be driven by organizational factors.

Poor organizational processes and culture, which can be driven by governmental pressures, and bad relationships with employers, supervisors or coworkers leave most employees feeling dissatisfied.

Survey findings from the Ministry’s human resources strategy report showed declining satisfaction with internal communication from 2010 to 2017. Subsequently, employees had poor perceptions of organizational support, commitment and employee relations.

Organizations struggle to maintain fast and responsive lines of communication because, for many, frontline workers have surpassed the number of administrative staff members. Additionally, of the 84 agencies surveyed, 11 per cent didn’t even have a human resources manager.

The number of employees per supervisor has also increased, with some supervisors overseeing as many as 40 workers. This makes it more difficult to develop strong relationships and provide individualized feedback.

In tandem with faulty lines of communication, most agencies do not have a participative work culture to encourage employee input in decision-making processes.

Within health care, frontline workers say they should be able to contribute to organizational policies considering they directly provide the services and know the needs of the clientele best.

But about 40 per cent of employees from the HR strategy report felt their organization didn’t care about, nor would they implement, employee suggestions on how to improve services.

Revisiting Hickey’s notion of prosocial motivation, it’s understandable that DSWs would want to have a say in organizational operations.

Approaching one’s supervisor often proves to be even less helpful, with many workers feeling they are unable to confide in managerial staff about workplace or personal challenges. Those who do so typically find their concerns go unacknowledged.

Employee relationships may also be strained because of the majority of frontline workers being female, and the majority of supervisors and managers being male. When employees aren’t getting along with upper management, they tend to lean on coworkers which can sometimes generate further group-based hostility toward their superiors.

Support workers at CLASS said it was important for them to have a strong team that they could lean on if they were having an off day.

“If you don’t have a good team, it’s almost impossible to not get burnt out,” Tori said. “Because if you’re not working with people that have your back or support you, then you feel alone all the time. And you can’t work alone all the time in this field.”

Yet, paradoxically, low retention rates and high turnover make it increasingly difficult to maintain strong team dynamics.

Hickey said that while some organizations need a culture shift, there are others that are trying to be progressive, yet find themselves restricted and pressured by governmental austerity.

“Ultimately this is all driven by government funding,” Hickey said, adding that even Ontario’s more than 29,000 long wait list for residential and community services is a product of finite financial resources, not labour supply.

“Organizations may have the right philosophies, the right cultures, the right intent, but they don’t have the resources. The system doesn’t have the resources to deliver on what that hope is,” he said.

A lack of funding, along with perpetual cuts, have pushed agencies to place greater weight on managerialism and budget priorities, versus focusing on the services they offer.

Representatives from the Ministry of Community, Children and Social Services acknowledged recruitment issues, but did not address burnout, turnover or any of the poor job characteristics in the field.

Additionally, they said that since agencies are the employers, it’s up to them to improve working conditions.

But, Vito Facciolo disagreed with the Ministry’s comments, and echoed Hickey’s arguments:

“They could say it’s up to the agencies, and of course it is, you create an environment, but you have to have the resources to be able to make a workplace attractive to people,” Vito said. “There is a big role that the government can play in making our workforce more stable, and that is giving us the subsidy that would allow us to give workers fair wages and benefits.”

Rather than dedicating money to agencies, the Ontario government continues to shift towards a direct funding model, known as passport funding. This gives the money directly to family members or the person with a disability so they can choose the services they want. Due to this, there’s been a growth in the informal labour market, where more families are personally employing DSWs for at-home care.

Though workers in these positions may enjoy better employer/employee relations, there is virtually no regulation or training to support them in their work.

In April 2019, the Progressive Conservative government of Premier Doug Ford announced cuts of up to one billion dollars to the Ministry of Children, Community and Social Services over the next three years. At this time, it’s still unclear whether these cuts will affect the developmental services sector.

Job Characteristics

With potential cuts looming, agencies will find it even more challenging to recruit new workers and retain the ones they have.

As it stands, workers gross less than $40,000 annually, a salary level that typically remains stagnant for several years. Despite a large portion of the workforce being unionized, benefit packages also suffer as they are not standardized across organizations.

Yet the largest factor driving turnover is the prevalence of part-time and casual work. According to HR managers, 62 per cent of DSPs and 53 per cent of DSWs are casual or work part-time hours. On average, part-time employees work about 30 hours per week. After a decade of working in the sector, only half of DSPs get hired on a full-time basis.

In order to maintain a living, nearly 42 per cent hold more than one job — a rate that is five times higher than the average for multiple job holders in Ontario’s health and social services sector.

Part-time work dominates the sector because of a tight labour market and the inability of agencies to financially support full-time employees.

A 2017 survey report by the OASIS (Ontario Agencies Supporting Individuals with Special Needs) labour relations committee found that organizations cut almost 5,000 staffing hours, more than 100 staff positions and they temporarily or permanently shut down 30 programs. All of this done, say the organizations, to balance higher operating costs.

Many organizations also cut back on training and development while maintaining fewer staff to support the same number of people. These changes reduce quality care and increase workload for the remaining employees.

In the comments section of the OASIS survey, agencies described low staff morale, and increased stress due to high workloads and job insecurity.

“So they’re saying, well we want to address the burnout, but we still want you to work for crappy pay and long hours without much discretion about what you’re doing,” said Dr. Michael Leiter, organizational psychology professor at Deakin University in Australia. “Implicit in that is that your work is not particularly important. That’s not a great message to give people if you want them to be fully engaged, rather than burnt out at their work.”

Burnout: The Worker

Panic attacks during his shift, feelings of exhaustion and isolation, and difficulty controlling his emotions indicated to Andrew that he was burning out.

“Every single day you go to work and are like, ‘ok, I’m essentially having a panic attack right now. That can get pretty tiring — mentally exhausting, emotionally exhausting,” Andrew said.

According to Leiter — who is internationally known for his research on burnout — people experience three distinct states: exhaustion at the start of the work day, feeling cynical and disengaged, and feeling unaccomplished at work.

This generates symptoms that can disrupt all aspects of a person’s life.

“Your performance deteriorates, as well as your health and certainly your happiness when you’re going through all of this,” Leiter said.

Research on burnout’s health effects on DSWs is limited, especially within a Canadian context. But for the most part, burnout manifests itself in similar ways across occupations.

The chronic exhaustion aspect increases the likelihood of stress-related illnesses and infections, specifically headaches, the common cold, the flu, muscle tension, high blood pressure, and digestive and cardiovascular disorders.

Yet, more often the symptoms have mental health consequences, leading to sleep disturbances, depression and anxiety. Research has found that those with increasing burnout scores were at a greater risk of being admitted to hospital for mental health issues.

A study in the U.S. confirmed that the more stressed out DSPs were, the more likely they were to be depressed. Key stressors were heavy workload, lack of organizational involvement and the degree of their client’s disability or level of care required. Those who had support at work, either from a supervisor or co-worker, felt less hopeless and depressed.

Another found that of 103 DSWs, 43 per cent were at risk of needing psychiatric assessments.

One of the precursors to depression and anxiety is the act of rumination or over-thinking. Though Tori said she has never experienced burnout per se, she has found herself prone to rumination when helping a client transition from their family home into a group home at CLASS.

“When you take your work home with you, you’re distracted, my mind’s racing,” Tori said. “I’m worried about oh, well did you send out those emails? Is he going to be okay tonight? He’s with three different staff that he’s never met, maybe I should have stayed later.”

This experience leaves her with conflicting emotions.

“You feel guilty for leaving your job at the end of the day,” she said. “But I mean, that is part of life right? You leave your job. Nobody can be at work 24.7.”

With any healthcare occupation, workers struggle to keep their emotions at bay. When workers burn out it usually becomes a lot more difficult for them to compartmentalize and mask their feelings.

Research shows that workplace stress comes with controlling one’s emotions on the job — specifically how people must alter their emotions to be appropriately professional during personal care tasks. Doing so causes emotional strain and exhaustion, especially if there’s no way to properly process or handle these emotions.

“And I think when you take care of people in any field, that can happen and you really have to step back and remember that no matter how much you care, it’s your job,” Tori said. “And when you leave here you have to leave it at the door. And when you come back in tomorrow morning, you’re full force back on, everything’s here.”

But keeping work life and personal life separate is usually a lot easier said than done.

Most support workers from CLASS, including Andrew, spoke about how their work has left them unable to be in the moment with family or friends or to enjoy personal downtime. Emily said it felt impossible to leave work because even at home she’ll get texts from coworkers asking about certain clients.

According to Dr. Leiter, for those who are mildly burnt out, recovering and returning to the job is possible, but the person needs to be supported so their day-to-day work-life changes.

For those who are severely burnt out, Leiter said the best way to recover is to completely change career paths.

“I find that most people who’ve been really severely burned out and recovered from it, not only left their organization but they left that whole career path, that occupation, and have gone a whole different route,” Leiter said.

“When you get the whole cluster of cynicism, with exhaustion, with discouragement, few people can go back to the same workplace and be fulfilled.”

Burnout: The Workforce & Services

The factors driving burnout are the same ones causing low retention and high turnover.

Turnover costs the province’s developmental sector an estimated $18 million annually, with 22 per cent of casual and part-time staff leaving in any given 12-month period, and 12 per cent of full-timers.

Not only does turnover impact the organization, but it significantly affects the people being supported. Those who experience changeover of DSWs have poor outcomes compared to others. Unlike their peers, they experience more insecurity, are less likely to realize their personal goals or interact with the community, and have more difficulty maintaining relationships with people.

But if burnt out staff don’t leave, then they’re probably providing suboptimal care.

The 2014 auditor general report found that between 2008 and 2013, alleged abuse or complaints of mistreatment increased by 92 per cent, to 451 reported occurrences in residential homes of community living agencies. The highest reported category of 2013 was the use of physical restraints. Whether these findings have been a direct result of worker stress and burnout is unknown, but higher levels of burnout do produce stronger negative feelings towards patients.

While Andrew never said so directly, his inability to provide high quality care was one of the reasons that he quit.

“I consider myself to be a kind and loving person, I consider myself a patient person, but I got to the point where I felt like I wasn’t doing a good job anymore, specifically to some of these individuals that I was supporting,” Andrew said. “I realized that my work or my ability to support was declining rapidly and I wasn’t treating the people that I was working for originally with the amount of respect that I should have been.”

Unlike many others, Andrew realized this and took it as a sign to step away. Having other career opportunities available meant that Andrew was able to leave. He was fortunate in that regard. Most people don’t have a backup plan or option.

The Way Forward

They say money won’t solve your problems, but for the DSW workforce it just might.

It seems readily evident that the sector requires more government funding to continue to function, and to do so at a higher standard. Larger subsidies for agencies could provide fair wages, better benefits, more training and open up full-time positions, all of which would make the job more appealing, and the career, a more respectable one.

While working conditions can improve with more funding, a more complete solution depends upon more than just money.

Though it’s evident that organizations are understaffed, the Ministry of Children, Community and Social Services doesn’t even know the full extent of the problem.

"The greater danger comes from what you don't know, you don't know. And if you're not tracking numbers, you don't know the extent of the problem as well as you could."

“There’s no requirement from the ministry about measurements,” said David Ferguson, who chairs the OASIS Labour Relations committee which oversees the operation and management of 193 community living organizations across Ontario. “We count dollars, we count spaces or beds and that’s about the extent of it.”

A potential way to track workers would be through licensing them.

This would not only help standardize wages and benefits across organizations, but it would create necessary professional hierarchies. For example, DSWs would be professionally distinct from PSWs and vice versa.

“These people [DSWs] are phenomenal individuals who really, truthfully put every single ounce of who they are into their job for our most vulnerable, and no one looks out for them,” said Miranda Ferrier, adding that a license would certify the career and make it more desirable.

DSWs would then be required to have certain credentials and the field would become a recognized profession.

In addition to this, changes on an organizational level need to occur — ones that focus on burnout prevention rather than treatment.

Michael Leiter said organizations need to invest in a culture that favours the frontline worker and revives employment relations.

“What we really have to do is to change things so that they align much better with how people really want to be doing their work,” Leiter said. “It’s much more responsive and meaningful for people that way.”

He said that workplaces need to be flexible to cater to personal needs and a healthy work-life balance, while also being responsive and making meaningful changes that actually work.

Above all else, this translates into giving people a significant voice within their organization.

“That usually means giving them more latitude and more sense of initiative,” Leiter said. “People like feeling that some of the time they are the ones that are making things happen, that they aren’t just simply responding to the directives that are coming their way, but that they’re actually initiating things.”

Research has shown that when DSWs are able to make decisions and have some control over the agencies’ care strategies, they’re more likely to commit to the organization.

Hickey’s reports also outlined several areas of improvements that focus on strengthening employment relations. This includes ensuring a participative work culture, with a focus on communication and competency-based or person-centered training. Better communication improves retention and keeping workers’ training up to date ensures they are prepared with the latest resources and strategies to excel in the workplace.

The human resource strategy report proposes that agencies practice quality improvement and organizational strategies that focus on strong leadership, and support diversity through cultural competence. Additionally, they should be able to effectively use technology, and embrace evidence-based practices.

Workshops or strategies to improve supervisor-worker relations and to mitigate heavy workloads may also be areas of focus.

But no one solution fits all. Agencies need to survey the workers at their own organization to better understand employee concerns, and then decide how to best move forward

Unfortunately for Andrew, there’s no change big enough that can bring him back to the DSP workforce — at least not for now. He said the industry still has a long way to go before it’s able to support the workers just as well as they support people with disabilities.

Yet the work and the people he has helped still hold a special place in his heart.

“It’s funny in life because when you get something that has such a really low low, it’s bound to have such a really high,” Andrew said. “It just works out for everything like that and with this industry you can really gain satisfaction from it, but it can quickly be destroyed at the same time.”