Tanner Morton

On March 19, the Ryerson Communications Centre filled with journalists and news junkies, attending yet another event attempting to confront the uncertain reality of journalism in Canada.

It happened also to be the day of the federal budget release, where the government of Canada outlined its upcoming plan to fund journalism in Canada. March 19 was altogether a day filled with plans to save the Canadian news industry.

At Ryerson, the title of the evening’s panel was “Journalism: All Shook Up”. Each speaker used their time to deliver thoughts on what could save an industry in crisis.

A theme gradually emerged, and as the evening concluded there seemed to be a consensus among panellists that the massive media chains of yesteryear were no longer sustainable. What they called “fragmented media” was going to be the way forward.

The long, slow death of traditional journalism has been reported in Canada since the earliest, most tentative steps of the “information superhighway” —the world wide web— what we now know simply as The Internet.

Moving from a long-established, stable, profitable, advertising-based business model, to one predicated upon the ever-shifting sands of digital-first-whatever-that-means-and-by-the-way-who-is-paying-for-it, was never going to be straightforward. Or profitable. Or, a pessimist might suggest, even sustainable.

The shift to digital has dried up traditional streams of advertising revenue, and the national newspaper chains that still serve as some of Canada’s largest news organizations are closing outlets or scrambling to save whatever lingering publications still operate across the country.

Trying to find a silver lining

The Local News Research Project, a crowd-sourced initiative that keeps a check on local outlets in Canada, reports that 275 news outlets have shut down since 2008. In their place, 105 new ventures have sprung up.

While these numbers paint a troubling picture, the goal of the conference at Ryerson wasn’t to focus on the difficult conditions facing Canadian journalism. Instead, it was to look for positive developments in a rapidly changing industry, and maybe predict where the industry might be headed. Each speaker used their time at the podium to deliver their thoughts on how journalists can weather the storm, and how emerging news ventures are innovating to keep afloat.

The optimistic view is that the scaling back of traditional media organizations creates plenty of holes that need filling. The challenge then is to fill in these spaces with sustainable solutions.

Each of the panelists had their own niche approach to that challenge, and rarely did their ideas overlap. Hyper-local outlets shared the stage with networks focused on disseminating stories across Canadian newsrooms, and organizations aiming to change how stories are reported.

Back to Local with The Pointer

The Pointer is a Brampton-based online publication produced since 2018 by former Toronto Star reporter San Grewal. It aims to bolster the coverage in one of Ontario’s largest cities in the Greater Toronto Area. Grewal went into the enterprise feeling that the city of Toronto didn’t need yet another news outlet, but surrounding communities such as Brampton did.

“One of the things I started to notice was that local news started to contract, and not just the legacy platforms but smaller local dailies, long-standing ones like The Guelph Mercury folded, and other outlets started to withdraw from the news game,” said Grewal.

This was because the large players, such as Torstar and Post Media, saw their advertising revenues plummet, and cuts had to be made to their newsrooms in smaller communities.

Even the local news outlets that were able to keep afloat such as Brantford Expositor, were cut to the quick. Chains sent out journalists from their big-city newsrooms to report stories they deemed newsworthy, but the coverage wasn’t the same.

“There is really an inability for larger platforms, national platforms to be able to get into the granular stories of the local market.”

– San Grewal The Pointer

The NAFTA renegotiations in 2018, for example, were a national focus when The Pointer was first established. Grewal said that even though impacted industries such as aluminum— vital to automotive plants in Brampton— were at the centre of the talks, there was little coverage of this angle for local audiences. Stories such as this were Grewal’s inspiration for launching his Brampton-focused newsroom.

Without going into specific numbers, Grewal says that The Pointer has been a sustainable business since its launch. But “sustainable” is not the same as “profitable”, and just how sustainable The Pointer is, is hard to know. Grewal won’t say, and public financial reports are unavailable. Whether the model is viable in the long term, with the potential to take hold and spread to other under-served local markets, is anybody’s guess.

Changing the Conversation

Local coverage isn’t the only facet of journalism that has been scaled down as traditional outlets look to cut costs. Articles featuring in-depth analysis have been replaced by work that requires fewer resources. Luckily, there are organizations that look to provide newsrooms across Canada with deeply researched pieces, absolutely free. Well, sort of free.

The Conversation debuted in Australia in the summer of 2010. It was marketed as a platform where academic research would intersect with traditional journalism. The Conversation Network has since expanded with hubs opening in different countries. The Conversation Canada started operation in 2017.

From a trendy co-working office in downtown Toronto, editor-in-chief Scott White explained the origin of the Canadian branch. As we spoke, other editors popped in to introduce themselves before heading to the cafe where they’d grabbing a coffee, snagging a table, and getting down to work.

He is no stranger to traditional Canadian media, having worked for national heavyweights like the Canadian Press and Post Media.

“I was editor-in-chief at CP for a billion years,” said White. In fact, it was 15, and such a long run in newsroom leadership set him up nicely for a job that takes scholarly output, repackages it, and distributes it as journalism. In the role, White collaborates with dozens of publications to make sure that stories reached the greatest number of readers possible.

White said that many people forget that CP used to be a non-profit cooperative before it was restructured into a for-profit business in 2010.

In the co-op days, member newsrooms would share stories among themselves. Part of White’s responsibilities was to work with different publications as partners, not as papers under a corporate structure. Now that White is leading The Conversation in Canada, working co-operatively with members has re-emerged as a core responsibility of his job.

“There’s a number of the same issues.You want to understand what’s going on and keep the members feeling relevant, and that they’re a relevant part of the organization.”

– Scott White, The Conversation Canada

In the case of The Conversation, the members are universities and think tanks that pay to belong to the organization. For their buy-in, member universities and think tanks gain access to sophisticated tracking and engagement tools, enabling them to measure and assess those most valuable of intellectual assets, impact and reach. The content is licensed under Creative Commons and as such is free to the public. Academics can publish even if their own university isn’t a paying member, but it limits the tracking data that are available from The Conversation.

All stories published by The Conversation Canada can be republished by any news organization across the globe, with proper accreditation.

“It’s different than the strategy that other organizations are doing where they’re putting up walls,” said Lisa Varano, audience development editor at The Conversation Canada. “We give away all of our content for free to anybody who wants to republish it.”

Each story from The Conversation has a small chunk of embedded code that is used to track how it is shared. Writers, and their host university, can then see how their article spreads across the web. Academics can use this information to gauge where their work is gaining traction, which could, in turn, help them strategize where to seek future funding.

“There’s this whole thing in academia called ‘knowledge mobilization’ or ‘knowledge transfer’,” said White. “It’s a big thing now because academics want to make sure that their work is getting out to the general public.”

It may surprise many that the most frequent republisher of Conversation content is The Weather Network, followed by Macleans and Global. Varano says she believes the science-focused content provided by The Conversation is popular because there are not always people with deep scientific knowledge or understanding in modern newsrooms.

Since The Conversation Canada launched, according to White, their content has been republished by over 300 different publications across the globe.

Republishing has allowed writers and content creators to see their work reach well beyond Canada, and with an average readership of 1.3 million views per month —a 55 per cent increase from the previous year— that reach is only expected to grow.

When the Canadian publication began, Verano said that they were able to tap into the existing international Conversation network for republishing opportunities.

Compare this to the traditional idea of newsrooms fiercely protecting their exclusives from the competition. For profit-driven publications, the worry about getting scooped by the competition trumped much else. By competitive necessity, newsrooms protected their exclusives. By contrast, as a not-for-profit operation, The Conversation is focused not on generating revenue from an audience — that aspect, so necessary for survival, is covered in the business model by the membership buy-in — but instead on their stories being engaged by the greatest number of readers.

“We’re giving things away because it’s our mission to get that information out there and improve the information that’s out there.”

– Lisa Varano, The Conversation Canada

This strategy allows Canadian news organizations to benefit from the work produced by academics and made available by The Conversation, without the need for a centralized corporation. Newsrooms can pick articles that suit their audience without devoting additional resources to covering niche topics.

White said that the core goal of The Conversation Canada is to provide detailed analysis and information to the public, and not to advocate for a particular stance or point of view.

“Solutions” Journalism? “Advocacy” Journalism? What’s going on here?

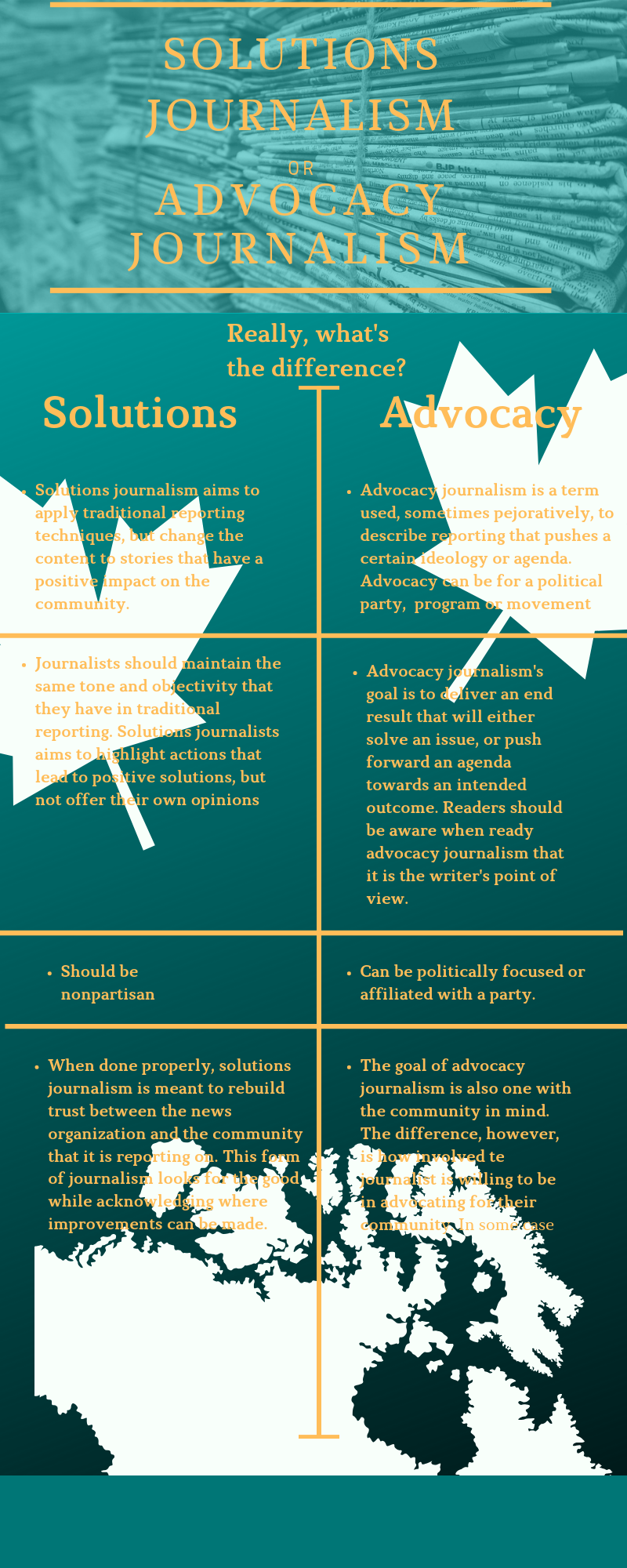

Advocacy journalism remains an uneasy topic for journalists. Journalism schools teach that a proper reporter must remain objective unless they are specifically writing an opinion article. Navigating the space between journalist and activist has become increasingly difficult with the rise of “solutions” journalism.

The term “solutions journalism” refers to the notion that instead of reporting on the seemingly constant negative events happening in the world, journalists should endeavour to publish stories that reflect positive change and provide readers with how it was accomplished. Not everything needs to be doom and gloom.

While the idea of solutions journalism may not be well known by every journalist, it isn’t a new style of reporting. In a 1998 article for the Columbia Review of Journalism, Susan Benesch explored what she characterized as “reporting on efforts that seem to succeed at solving particular social problems.”

The criticism against this form of journalism is that it is not, in fact, journalism at all. The stories are too treacly. Events and trends that need to be taken seriously, and understood deeply, are instead rendered into derivative pieces of fluff. As cautionary reports and deep dives into the latest piece of government corruption, journalism that spotlights the better parts of society may be written off as unedifying.

Environmental degradation. Democracy in retreat. The rise of nativistic populism. Enduring racism, Islamophobia, and anti-Semitism. Are these not the essential stories of our time? And, if so, how are we to package them in a way that is —in the language of solutions journalism —uplifting?

And even if that question is unanswerable, is it even the role of journalism to “uplift”?

Since Benesch’s piece was published lightyears ago in a largely pre-internet age, an organization has formed to champion the cause of solutions journalism.

“It’s not necessarily this brand new revelation, it’s just changing the content,” said Jules Hotz of the New York-based Solutions Journalism Network.

“It’s not opinion journalism,” said Hotz. “Journalists are not coming in and making an argument for a program or cause. Instead, they are reporting with an eye to rigour, the same things they bring to non-solutions journalism. They’re reporting on where that solution, or response, succeeds and where it fails.”

The Solutions Journalism Network (SJN) calls itself an organization “focused on training journalists to approach their stories from an alternative solutions-based angle”. Hotz said that equipping journalists with the skills needed to pursue this style of reporting is SJN’s main aim.

While solutions journalism is a term that has been used by organizations such as The National Observer and The Discourse, no one calls themselves a solutions journalist. Journalists can’t build their careers only reporting solutions-based stories.

In fact, Hotz said it would be next to impossible for a newsroom to report only solutions stories. This is why it should be seen as an approach to reporting, rather than a distinct model.

Through online and in-person workshops, would-be solutions journalists are taught how to use this approach in their work. According to Hotz, solutions journalism still considers the same questions as any other form of reporting.

“What kind of journalism techniques does it take to do solutions journalism, who do you interview, where do you look for stories, how do you make sure that you’re not doing advocacy and that you’re actually covering this with rigour?”

–Jules Hotz, Solutions Journalism Network

SJN has a database of more than 6000 stories from around the world that it classifies as solutions journalism. Stories are listed by location, and 127 of the 6000 are from Canada. That number —that proportion — is small, but it is growing.

The benefit of the database, aside from allowing journalists to see the reach of their story, is that any reader can see what previous work has been done on any given issue and its effect.

“It’s useful for journalists, but we also really tried to build the platform for people who are not journalists as well,” said Hotz, and that one of the key groups would be policymakers. These individuals, or more likely their staff, can search through the database to find how other communities have dealt with similar problems and adopt solutions to find their own resolution.

The SJN database is still being developed. One of its goals is that it will eventually allow users to see how SJN stories have brought about policy change in communities around the world.

“I think that communities gravitate towards solutions journalism because they are so used to reporters coming in and just talking about the problems,” said Hotz. “Communities think that journalists are just there to get clicks.”

In addition, Hotz says that solutions journalism is intended to cover communities that are thriving and what steps have been taken to reach that point. The goal, she says is to create a network for communities looking to solve problems such as air pollution and homelessness. The whole point —the raison d’être—of solutions journalism is, as the label suggests, to explore solutions to such vexing social and existential problems.

Hotz says solutions journalism can also be a new way to hold power to account. Practical examples can be presented to policymakers, by those very citizens informed by solutions journalism. Hotz says that it equips citizens with practical examples they can present to their own elected officials during policy consultation.

“It’s not just ‘we want you to change this thing,’ but instead ‘we want you to change this thing and we know how to do it because it worked in this other community,’” said Hotz.

So if that is what we now understand to be “solution” journalism, what about its better-known forerunner, “advocacy” journalism?

SJN draws a hard line between solutions journalism and advocacy

Perhaps it comes down to the long history of advocacy and partisan journalism in Canada.

As it was in much of the Western world, in Canada historically, political parties and news organizations working in partnership was one way in which “journalism” manifested itself. George Brown’s The Globe, a precursor to The Globe and Mail, was often used by Brown’s Reform party to push its agenda.

It was only during the mid-20th century when the newspaper advertising model that was to eventually stand in stark, suffering, and ultimately failing relief to the revolutionary 21st-century internet model took off, that newspapers were able to distance themselves from the political parties that were once their key financial supporters. Up to that point, it was understood that major papers in Canada would be comfortable bedfellows with the major competing parties. Such a notion would cause current-day stalwart objectivists to shudder, but it’s an important part of Canada’s journalistic history.

Funding for the Future: Is a government gift horse the way forward?

In the wake of a half century or more of the “traditional” journalism model, whose reliable profit-generating capacity often created vast fortunes for publishing families or corporations, what comes next?

Government charity? Perhaps.

In its budget announcement of November 22, 2018, the federal government made a vague commitment to invest in the future of Canadian journalism. It took a few more months before tentative details emerged.

The lede: There would be a new influx of money: $595 million over the next five years.

An independent panel would be established to recommend which media organizations qualify for any of the money. Those organisations would be deemed a “Qualified Canadian Journalism Organization (QCJO). Canadian newsrooms wishing to qualify as a QCJO would have to employ at least two journalists who “deal at arm’s length with the organization”.

This criterion of “at arm’s length” appears to work in favour of larger, existing legacy operations. Put bluntly, if you’re starting a newsroom to fill a reporting gap left in your local community by the closing of the local paper, unless you have the initial resources to employ two journalists who are not also involved in the business side of the newsroom, you’re out of luck. And not many journalism start-ups are going to have those kinds of initial resources.

And anyway what makes a journalist? Is there even a definition? Journalism in this country has never been a regulated profession; a point of pride for many in the field because it allows, in theory, journalistic independence.

Another criterion to qualify as a QCJO is that the newsroom can’t be focused on niche subjects. While this in no way precludes journalists covering local affairs from receiving a subsidy, it could mean that special interest publications focussing on topics such as technology are left out.

The proposal does attempt to embrace smaller, independent, non-profit producers of journalism by allowing them to apply for charitable status.

Currently, The Walrus Foundation is the only journalistic publisher in Canada that qualifies as a non-profit organisation.

Beyond this narrow qualifier of non-profit status, are other proposed tax strategies directed at newsrooms that remain within the for-profit sector.

The first targets the Canadian consumer, who will be able to claim a credit for subscriptions to Canadian digital news. The maximum tax credit will be $75 but will only apply to the purchase of online written journalism. Podcasting and online video providers are left out, with no explanation provided by the federal government.

Tax credits aren’t to be limited to the subscribing public. There is a plan to introduce a labour tax credit as well for publications to claim.

The labour tax credit carries the most detailed provisions at this point, with qualifying employees working for at least 40 consecutive weeks a year and spending 75 percent of their required 26 hours per week “engaged in the production of news content.”

One of the main issues with the new labour credit is that there is no incentive for hiring new employees. Organizations will need to invest almost a year of employment in new hires before they qualify for the labour credit. While organizations that employ a larger number of qualifying journalists will benefit more than smaller employers, practically speaking, publications can save the money they might otherwise have originally spent on employees, and instead award their upper executives with larger bonuses.

Who is to say they can’t? Considering that in 2018 Postmedia CEO Paul Godfrey was awarded a $1.2 million bonus even as he was campaigning for greater government funding for legacy news publications, this isn’t a ridiculous conclusion.

None of this means necessarily that legacy publications will be the biggest beneficiaries, but as all of these publications do focus on print publishing, they are poised to benefit with little change to their current business practices if the proposed plan goes through.

And that is part of the argument fuelling the critics of the federal government proposal.

To its supporters, the influx of more than half a billion dollars is a much-needed lifeline that will help save newsrooms across the country. And for communities that have watched their local coverage shrink, direct funding could help stem the tide of job losses.

But critics warn that establishing a direct funding model could calcify the journalistic landscape, slowing innovation and leaving journalism and journalists in the unattractive position of being reliant on government handouts. And given the always-differing priorities from one government to the next, usually along party or ideological lines, it could make for a very fraught existence. Ask anyone who has ever worked at the CBC.

It’s little surprise that new media ventures aren’t holding their breath waiting to be saved by subsidies from the Canadian government.

Back in Brampton at The Pointer, San Grewal says he will accept funding if it comes around, but he isn’t basing the financial stability of his newsroom on handouts from the government.

Meanwhile, at The Conversation Canada, Scott White and Lisa Varano aren’t concerned about most of the proposed tax changes by the federal government. As publishers relying on funding from participating academic institutions, they haven’t been hit by Facebook and Google taking away the majority of advertising dollars in the way traditional news sources have been.

This doesn’t mean, according to White, that they won’t try for non-profit status if the opportunity presents itself, but there’s a significant caveat that comes with any funding commitment in an election year. In the upcoming federal election in October, the governing Liberal party needs to win.

An Uncertain Future

There isn’t a single model of doing journalism that is going to save the news industry.

Publications will continue to struggle, and major traditional media sources will still try to find ways to keep operating in whatever parts of the world still embrace, in theory at least, the principle of a free press.

The new federal funding may end up saving Canadian journalism. That is what Liberal policymakers are banking on. Or it may end up stagnating journalistic innovation. That is what some of the would-be innovators say.

For the average, news-consuming Canadian, it is all likely to be unremarkable. Throwing money at a problem can only go so far, and the greater systemic issues of how to make news organizations viable will continue to vex the industry.

The fragmentation evidenced by the hyper-local efforts of The Pointer, or the shareable-journalistic-academia model of The Conversation Canada may be the future. Or perhaps the advertising-based models of yore will mount some kind of unlikely messianic comeback. But whatever it is to be, Canadians still need their news, maybe now more than ever.

== 30 ==